Women’s access to better pay is long overdue – why has it taken so long to get there?

The gender pay gap has been a thorn in the side of many women for far too long. It was created as an internationally established measure of women’s position in economy in comparison to men. It is the result of the social and economic factors that combine to reduce women’s earning capacity over their lifetime. It is not the differences between two people being paid differently for work of the same or comparable value.

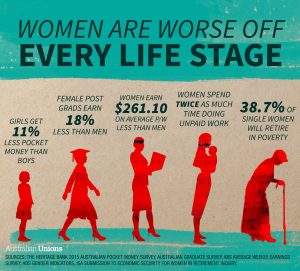

The gender pay gap is discrimination and bias in pay decisions; women in female-dominated industries have consistently attracted lower wages. Then women tend to have more time out of the workforce as they care for a young family or sick/ageing family members, which in turn impacts their career and earning capacity.

In 1969, the principle of ‘equal pay for equal work’ was introduced and then later on in 1984, anti-discrimination on the basis of sex was legislated. However, the gap still remains at around 14-19% or around $240+ per week. Some of the pay gaps are due to more men in managerial positions and occupational segregation.

The pay gap has only narrowed by approx. 2% in the last ten years. At that rate, it will take a century for women to reach equal pay. One theory is to consider banning employers from asking job candidates about their salary history and expectations in a bid to close the gap.

Whilst women represent 50% of the Australian population, they are only 45% of the workforce. But an interesting trend is seeing more females now completing schooling and over 55% entering tertiary institutions which indicates that there is a turnaround coming.

Women choose different occupations from men and there are large and persistent differences in the earnings of different occupations. All around the world, occupations like teachers traditionally pay less than occupations like engineers. So, gender differences in occupational choice affect gender differences in earnings. But why do women and men make different occupational choices? Are there not enough role models for women in higher-paying occupations? Are there barriers to female advancement in those occupations? The plain truth to these questions is YES. The glass ceiling still exists in some boardrooms. Moreover, even within high-paying occupations, women tend to be employed at lower levels of the occupational hierarchy.

Women also tend to choose to work part-time more than men especially once the responsibility of children comes around; this is a significant factor but allows the women to tend to the work associated with running a household and raising the children. That is unpaid work. Whilst paternity and maternity leave have helped with some of the penalties associated with having a family it is cited as a very important policy to reduce or eliminate the pay difference. Upon returning to work, women often find that it isn’t financially viable to work more than 4 days a week due to means-tested childcare rebates and family tax benefits – a further sacrifice financially. Another factor of inequality in unpaid superannuation. Employers do not pay superannuation for employees earning $450 or less per week and that is often the woman.

Sadly, there is still a lot of hidden discrimination, stereotyping and biases playing a role in the workforce. Even if we ignored the education effect, the occupational effect, the sector effect and all the other blockages that prevent women from forging careers, the gender pay gap in earnings still remains. Government policies, legal protections and changes in business practices (like regular pay assessments of earnings) are necessary to start to combat these gender pay gaps. Women who do show ambition and confidence are often negatively viewed as bossy, whereas a male [with the same behaviour] is viewed favourably. Regardless of any merit within the workforce, many promotions are granted to a male.

Even though women have increased their presence in higher-paying jobs traditionally dominated by men, such as professional and managerial positions, women as a whole continue to be overrepresented in lower-paying occupations. This may also contribute to gender differences in pay.

Despite all efforts from many angles to bridge the gap, it is still harmful to a women’s economic security and economic growth. This inequality contributes to lower family incomes and increased poverty among families with a working woman. With the increase of single women – with or without children – the pay gap holds woman back into poverty and constant financial struggles – a real concern as the years go by.

It is, therefore, more important than ever for women to get passionate about their money, they should be encouraged to take an interest, rather than taking it for granted or surrendering the responsibility to a partner. For divorcees, it is even more important for this growing group of women now facing real financial stress.

Women are forced to work beyond retirement age and usually living from pay-check to pay-check.

An RMIT University economist Leonora Risse notes the superannuation balance gap between men and women is about 34%. It’s contributing to a growing homelessness crisis among women aged over 55.

Without taking any action, the financial future for a woman is going to continue to have it’s struggles as changes are too slow to feel the real impact.

Philippa Hunt is a Woman on a Mission.

WiseGirls Money Academy was created after working as a qualified Financial Adviser for many years and deciding it was time to assist women who desired to learn and develop the self-empowerment to understand their emotional relationship with money, the skills and knowledge to save and invest. They wanted to learn how to create their own financial future and become financially capable.

The WiseGirls Money Mission is to provide the opportunity and place for growth and development of women of all ages in personal and financial skills in a supported female environment so that they take control of their future to reach their own financial independence.